2.3.3 From Least Squares to Nearest Neighbors

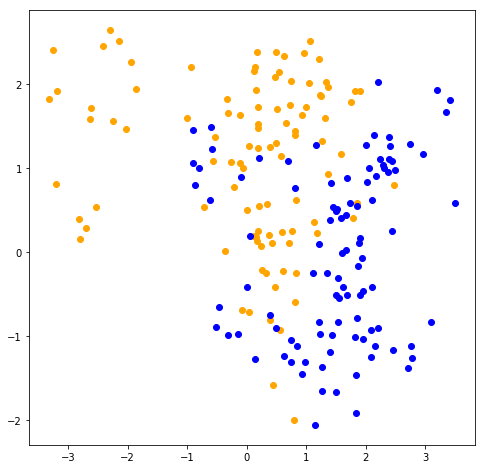

Generates 10 means \(m_k\) from a bivariate Gaussian distrubition for each color:

\(N((1, 0)^T, \textbf{I})\) for BLUE \(N((0, 1)^T, \textbf{I})\) for ORANGE

For each color generates 100 observations as following:

For each observation it picks \(m_k\) at random with probability 1/10.

Then generates a \(N(m_k,\textbf{I}/5)\)

% matplotlib inlineimport randomimport numpy as npimport matplotlib.pyplot as plt= 100 def generate_data(size, mean):= np.identity(2 )= np.random.multivariate_normal(mean, identity, 10 )return np.array([/ 5 )for _ in range (size)def plot_data(orange_data, blue_data): 0 ], orange_data[:, 1 ], 'o' , color= 'orange' )0 ], blue_data[:, 1 ], 'o' , color= 'blue' )= generate_data(sample_size, [1 , 0 ])= generate_data(sample_size, [0 , 1 ])= np.r_[blue_data, orange_data]= np.r_[np.zeros(sample_size), np.ones(sample_size)]# plotting = plt.figure(figsize = (8 , 8 ))= fig.add_subplot(1 , 1 , 1 )

2.3.1 Linear Models and Least Squares

\[\hat{Y} = \hat{\beta_0} + \sum_{j=1}^{p} X_j\hat{\beta_j}\]

where \(\hat{\beta_0}\) is the intercept, also know as the bias . It is convenient to include the constant variable 1 in X and \(\hat{\beta_0}\) in the vector of coefficients \(\hat{\beta}\) , and then write as:

\[\hat{Y} = X^T\hat{\beta} \]

Residual sum of squares

How to fit the linear model to a set of training data? Pick the coefficients \(\beta\) to minimize the residual sum of squares :

\[RSS(\beta) = \sum_{i=1}^{N} (y_i - x_i^T\beta) ^ 2 = (\textbf{y} - \textbf{X}\beta)^T (\textbf{y} - \textbf{X}\beta)\]

where \(\textbf{X}\) is an \(N \times p\) matrix with each row an input vector, and \(\textbf{y}\) is an N-vector of the outputs in the training set. Differentiating w.r.t. β we get the normal equations:

\[\mathbf{X}^T(\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}\beta) = 0\]

If \(\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X}\) is nonsingular, then the unique solution is given by:

\[\hat{\beta} = (\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X})^{-1}\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{y}\]

class LinearRegression:def fit(self , X, y):= np.c_[np.ones((X.shape[0 ], 1 )), X]self .beta = np.linalg.inv(X.T @ X) @ X.T @ yreturn self def predict(self , x):return np.dot(self .beta, np.r_[1 , x])= LinearRegression().fit(data_x, data_y)print ("beta = " , model.beta)

beta = [ 0.52677771 -0.15145005 0.15818643]

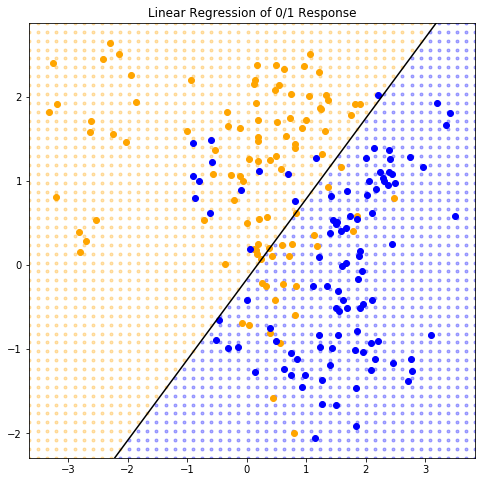

Example of the linear model in a classification context

The fitted values \(\hat{Y}\) are converted to a fitted class variable \(\hat{G}\) according to the rule:

\[

\begin{equation}

\hat{G} = \begin{cases}

\text{ORANGE} & \text{ if } \hat{Y} \gt 0.5 \\

\text{BLUE } & \text{ if } \hat{Y} \leq 0.5

\end{cases}

\end{equation}

\]

from itertools import filterfalse, productdef plot_grid(orange_grid, blue_grid):0 ], orange_grid[:, 1 ], '.' , zorder = 0.001 ,= 'orange' , alpha = 0.3 , scalex = False , scaley = False )0 ], blue_grid[:, 1 ], '.' , zorder = 0.001 ,= 'blue' , alpha = 0.3 , scalex = False , scaley = False )= axes.get_xlim()= axes.get_ylim()= np.array([* product(np.linspace(* plot_xlim, 50 ), np.linspace(* plot_ylim, 50 ))])= lambda x: model.predict(x) > 0.5 = np.array([* filter (is_orange, grid)])= np.array([* filterfalse(is_orange, grid)])"Linear Regression of 0/1 Response" )= lambda x: (0.5 - model.beta[0 ] - x * model.beta[1 ]) / model.beta[2 ]* map (find_y, plot_xlim)], color = 'black' , = False , scaley = False )

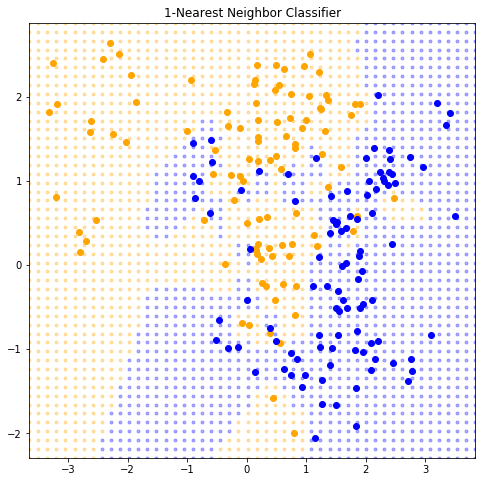

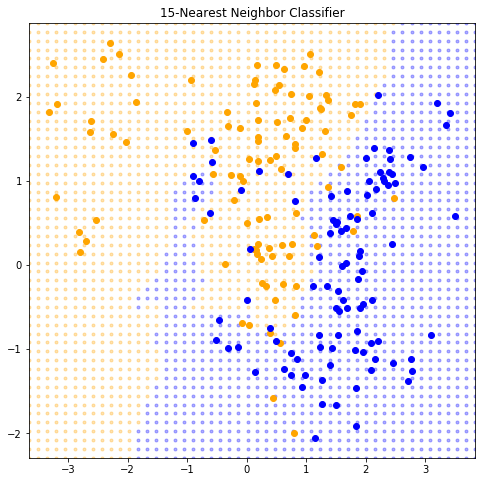

2.3.2 Nearest-Neighbor Methods

\[\hat{Y}(x) = \frac{1}{k} \sum_{x_i \in N_k(x)} y_i\]

where \(N_k(x)\) is the neighborhood of \(x\) defined by the \(k\) closest points \(x_i\) in the training sample.

class KNeighborsRegressor:def __init__ (self , k):self ._k = kdef fit(self , X, y):self ._X = Xself ._y = yreturn self def predict(self , x):= self ._X, self ._y, self ._k= ((X - x) ** 2 ).sum (axis= 1 )return np.mean(y[distances.argpartition(k)[:k]])

def plot_k_nearest_neighbors(k):= KNeighborsRegressor(k).fit(data_x, data_y)= lambda x: model.predict(x) > 0.5 = np.array([* filter (is_orange, grid)])= np.array([* filterfalse(is_orange, grid)])str (k) + "-Nearest Neighbor Classifier" )1 )

It appears that k-nearest-neighbor have a single parameter (k ), however the effective number of parameters is N/k and is generally bigger than the p parameters in least-squares fits. Note: if the neighborhoods were nonoverlapping, there would be N/k neighborhoods and we would fit one parameter (a mean) in each neighborhood.

15 )